Research for Everyone

Young people designing prototypes for new technologies, residents recording the urban sounds of their neighbourhoods, or people researching their everyday language: These are citizens being researchers. In Citizen Science, scientific projects are carried out either with the help of interested laypeople, or entirely by non-researchers. The Citizen Scientists formulate research questions, report observations, carry out measurements, evaluate data, and write publications. One key condition is compliance with scientific criteria. Citizen Science is beneficial to science as a whole, not only because it results in new research projects and findings, but also because it increases the public’s access to knowledge. Ideally, this type of citizen participation has the potential to make science more democratic and align it more closely with society’s needs. This in turn strengthens trust in science.

Four new Top Citizen Science projects approved

Strengthening trust in science is a declared goal of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), which has been supporting Top Citizen Science projects with up to €50,000 per project since 2016. Four new projects are now at the starting line. The wide range of topics covers the effects of digitalisation on our lives, the mining town of Eisenerz’s efforts to remain on the map, changes in Austrian dialects over time, and the development of new, sustainable technologies.

Giving citizens a voice in urban design

Cities are more than just buildings. They are living spaces where we come into contact with each other and agree on common values and principles. The art and architecture theorist Peter Mörtenböck has always been interested in understanding how new technologies change our living spaces and our coexistence. Data is playing an increasingly important role in shaping our cities. “Platforms and services such as Airbnb, Amazon, DriveNow, or Google Maps collect data on mobility and consumer behaviour and use this knowledge in cooperation with municipal administrations to create new transport systems,” explains Mörtenböck. The problem: In these data-driven processes, citizens are often deprived of a say. The “City Layers” project aims to change that. With the help of an app, residents can decide for themselves which data should be collected. For example, participants can record measurable information such as urban sounds at different locations in the city and combine these recordings with individual opinions and experiences. “In research and development, we often make assumptions when defining general interests, values, and attitudes. Afterwards it turns out that this fictitious public does not exist, making our results worthless. Including citizens, on the other hand, gives us access to a wide diversity of concerns and ways of thinking in the research process,” says the environmental psychologist, describing the added value of Citizen Science.

City Layers: Citizen Mapping as a Practice of City-Making

Peter Mörtenböck, TU Wien, Institute of Art and Design

Austrian dialects in transition

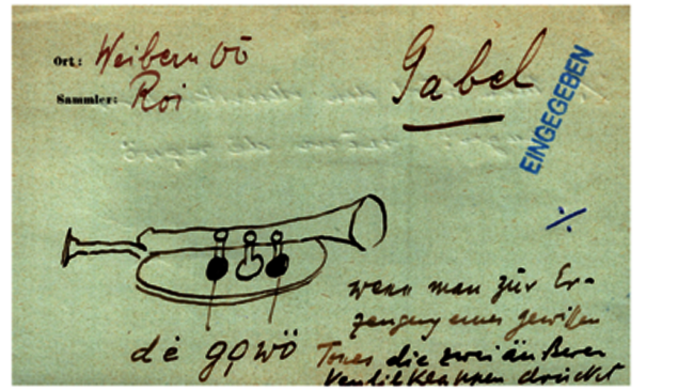

“Grüß Gott,” “Guten Tag,” “Hallo,” “Hi,” “Servus,” “Mahlzeit” ... Speakers need to choose a greeting before their first linguistic contact with another person. This example not only shows how varied the German language is, but also makes it clear: The speaker’s choice determines how the message will affect the recipient. “Speaking is always also a social act. It's often not what you say, but how you say it,” says Alexandra N. Lenz. A professor of German studies at the University of Vienna, Lenz is investigating the wealth of variants of the German language in Austria. In doing so, she sees language not only as a means of communication, but also as an important part of culture that is both identity-forming and subject to constant change. The project “The ABC of Dialects: Exploring Historical Notes Digitally" aims to process 100-year-old data on Austrian dialects and make it available online for the first time. The data is being sourced from handwritten texts and words on papers collected for the dictionary of the Austro-Bavarian dialect WBÖ; these texts are over 100 years old. Via an online platform, participants can access the scans of the handwritten texts, transcribe them, and evaluate them. Do I know the word? Has the use of the word changed? Do I still use the word in my own everyday life? “In linguistics, citizens have always played an important role. They not only provide information on language use, but also actively shape research questions,” says Lenz.

The ABC of Dialects: Exploring Historical Notes Digitally

Alexandra N. Lenz, University of Vienna, Institute for German Studies

New technologies for sustainable development

Our smartphones and other devices contain materials such as tungsten, tin, tantalum, and gold. All of these raw materials are mined in conflict regions, assembled into electrical circuits under unhealthy working conditions, and ultimately disposed of, usually after a short time, in contaminated landfills. Stefanie Wuschitz is researching new, sustainable technologies. The media artist works at the interface between art, research, and technology. In the project “Salon of Open Secrets” at the Vienna Museum of Science and Technology, she is working with young people to develop sustainable, fair, ethical technologies. First, participants visit inventors from all over the world in a virtual game, who provide information about conflict-ridden metals and their mining and propose alternative solutions. Afterwards, the participants conduct experiments and build real-life prototypes, which are presented online and discussed with experts on an international online platform. “In times of crisis, it is often the most unorthodox approaches that suddenly make an idea feasible. That's why I like to work with amateurs,” explains Wuschitz. In her work, the researcher also addresses the lack of communication between academia and the youth movement. “We want to harness the creativity and transformative work of young citizens and hope that the visions that emerge will expand our concept of future technology and, on the other hand, offer participants the opportunity to imagine an alternative future,” she says, describing her goal. The basis for this is democratic access to knowledge, so that the values, goals, and expectations of all can be heard. “There is an urgent need for young people, whose lives are particularly threatened by the climate crisis, to help shape public discourse,” she says.

Salon of Open Secrets

Stefanie Wuschitz, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Institute for Education in the Arts

Eisenerz - Staying on the map

Economic and structural changes in Europe since the 1970s and early 1980s have led to a decline in traditional industrial regions. Mining areas are particularly affected by shrinkage. The effects this has on a region can be seen in the Upper Styrian city of Eisenerz. With an average age of 54.6 years, it is Austria’s demographically oldest municipality. On the one hand, the high average age results in an increased need for care. On the other hand, ecological renaturation measures, efforts to preserve cultural institutions, and the fight against economic decline and vacancies are very labour-intensive. “Care and maintenance work is often done on site by unpaid volunteers,” says Karin Reisinger. The architect from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna explores the diversity of this type of work, focusing primarily on spatial care and maintenance practices that address culture, ecology, and society. “In a changing world with climate change, resource scarcity, and social injustice, it is important to learn from regions that have been coping with different forms of exploitation for a very long time and to see what strategies and practices they have developed,” she says of her motivation. To make these practices visible, Reisinger applies feminist strategies. In her project “Stories of Post-Extractive Feminist Futures,” citizens are invited to talk about their experiences of care in mining regions and to discuss their work. “Only through the intensive involvement of citizens can we include the diversity and complexity of living knowledge,” she says.

Stories of Post-Extractive Feminist Futures

Karin Reisinger, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Institute for Education in the Arts